Wrong Information on USCIS Website Resulted in Rejected DACA Renewal Application

A family’s wellbeing is threatened when a mother loses her DACA due to a government mistake

THE TORCH: CONTENTSBy NILC staff

FEBRUARY 26, 2018

The day after Christmas, while the rest of the country recovered from holiday celebrations, a 26-year-old mother of two sat helplessly while her Deferred Action for Childhood arrivals, or DACA, expired. Suddenly, she was no longer eligible to work in cleaning services and provide for her family, to which she contributed half of the household income.

Lisbeth met her husband and the father of her children at her family’s church while she was still in high school in Silver Spring, Maryland. Shortly before she graduated from high school, she gave birth to the couple’s first child. She has never feared deportation before. Now she cannot imagine it. She is terrified of being separated from her two U.S. citizen children and of being sent to live in El Salvador, a country that her family left when she was 13 years old because their lives were in imminent danger there.

A few years after graduating from high school, she applied for and was granted deferred action under DACA. Just weeks after the Trump administration announced on Sept. 5, 2017, that it was terminating the DACA program, Lisbeth gave birth to her second son. She mailed in her renewal application by two-day priority mail, and it was received at the Chicago lockbox well in advance of the administration’s arbitrary October 5, 2017, deadline for submitting renewal applications under its regime for terminating the program.

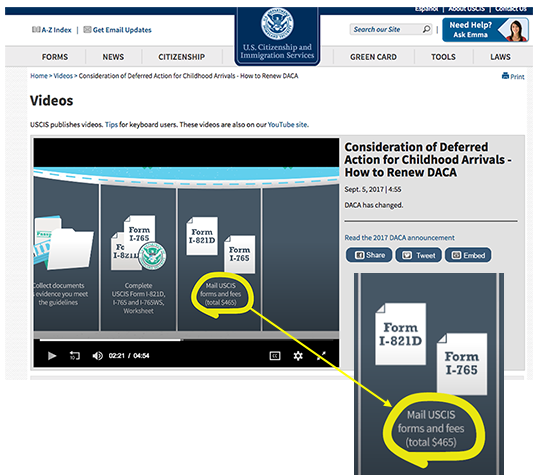

Lisbeth correctly followed the incorrect instructions in a USCIS video, which resulted in her DACA renewal application being rejected.

Lisbeth eventually received a rejection letter from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), saying that the fee payment she’d submitted with her application, $465, was incorrect, since the fee is $495. Lisbeth was confused, because in preparing her application she’d carefully followed the instructions she’d found in a USCIS video. When she rewatched the video to verify what her mistake had been, she saw that the mistake was actually USCIS’s: The video clearly said that the renewal fee is $465, not $495.

Because the rejection letter was accompanied by a green cover letter inviting Lisbeth to resubmit her application, she did exactly that, this time including a check for $495. A month later, she received another rejection notification saying that USCIS was no longer accepting renewal applications.

Lisbeth’s younger sister — who is also a DACA recipient — is graduating from high school this year, but her future is uncertain because her protected status expires in 2019. Lisbeth is now urgently asking Congress to create a permanent solution for people like her sister so they can continue their studies at the college level and contribute their maximum talents to the only country they’ve ever known — the only place they call home. And Lisbeth needs Congress to create a permanent solution so that her two young boys will not be left without the daily care of their mother, either because she’s been sent back to a place of instability and violence or because she can no longer provide for them.

The lives of Lisbeth and her family have been put in crisis by the Trump administration’s reckless termination of the DACA program and by incorrect information published by the very government agency charged with administering the process that would provide them some relief and protection.

It doesn’t have to be this way. To learn more about what you can do to help people such as Lisbeth, visit www.nilc.org, or call Congress at 1-478-488-8059 and ask your senators and representatives to vote on the bipartisan Dream Act now!